- Home

- Mohandas Gandhi

Autobiography

Autobiography Read online

DOVER BOOKS ON HISTORY, POLITICAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCE

Six-GUNS AND SADDLE LEATHER: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF BOOKS AND PAMPHLETS ON WESTERN OUTLAWS AND GUNMEN, Ramon F. Adams. (0-486-40035-2)

THE GIFT To BE SIMPLE, Edward D. Andrews. (0-486-20022-1)

THE PEOPLE CALLED SHAKERS, Edward D. Andrews. (0-486-21081-2)

GOD AND THE STATE, Michael Bakunin. (0-486-22483-X)

THE STORY OF MAPS, Lloyd A. Brown. (0-486-23873-3)

THE DWELLERS ON THE NILE, E. A. Wallis Budge. (0-486-23501-7)

THE BOOK OF THE SWORD, Sir Richard F. Burton. (0-486-25434-8)

HISTORY OF THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE, John B. Bury. (0-486-20398-0, 0-486-20399-9) Two-volume set.

THE DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF TUTANKHAMEN, Howard Carter and A. C. Mace. (0-486-23500-9)

ESSENTIAL WORKS OF LENIN, Henry M. Christman (ed.). (0-486-25333-3)

THE RIVER WAR, Winston Churchill. (0-486-44785-5)

THE MEDIEVAL TOURNAMENT, R. Coltman Clephan. (0-486-28620-7)

BUFFALO BILL’S LIFE STORY: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY, W. F. Cody. (0-486-40038-7)

THE WORLD’S GREAT SPEECHES: FOURTH ENLARGED EDITION, Lewis Copeland, Lawrence W. Lamm, and Stephen J. McKenna (eds.). (0-486-40903-1)

THE MEDIEVAL VILLAGE, G. G. Coulton. (0-486-26002-X)

THE EXERCISE OF ARMES: ALL 117 ENGRAVINGS FROM THE CLASSIC 17TH-CENTURY MILITARY MANUAL, Jacob De Gheyn. (0-486-4()442-0)

MY BONDAGE AND MY FREEDOM, Frederick Douglass. (0-486-22457-0)

AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF BATTLES, David Eggenberger. (0-486-24913-1)

LIFE IN ANCIENT EGYPT, Adolf Erman. (0-486-22632-8)

GREAT NEWS PHOTOS AND THE STORIES BEHIND THEM, John Faber. (0-486-23667-6)

THE ARMOURER AND His CRAFT, Charles ffoulkes. (0-486-25851-3)

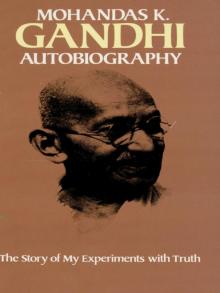

AUTOBIOGRAPHY: THE STORY OF My EXPERIMENTS WITH TRUTH, Mohandas K. Gandhi. (0-486-24593-4)

WOODROW WILSON AND COLONEL HOUSE: A PERSONALITY STUDY. Alexander L. and Juliette L. George. (0-486-21144-4)

ANARCHISM AND OTHER ESSAYS, Emma Goldman. (0-486-22484-8)

LIVING MY LIFE, Emma Goldman. (0-486-22543-7, 0-486-22544-5) Two-volume set.

THE DESCRIPTION OF ENGLAND, William Harrison. (0-486-28275-9)

UTOPIAN COMMUNITIES IN AMERICAN, 1680–1880, Mark Holloway. (0-486-21593-8) THE COMMON LAW, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (0-486-26746-6)

THE WANING OF THE MIDDLE AGES, Johan Huizinga. (0-486-40443-9)

THE TRIALS OF OSCAR WILDE, H. Montgomery Hyde. (0-486-20216-X)

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF THOMAS JEFFERSON, Thomas Jefferson. (0-486-44289-6)

MUTUAL AID, Peter Kropotkin. (0-486-44913-0)

NOSTRADAMUS AND His PROPHECIES, Edgar Leoni. (0-486-41468-X)

THE GREAT CHICAGO FIRE, David Lowe (ed.). (0-486-23771-0)

THE INFLUENCE OF SEA POWER UPON HISTORY, 1660—1783, A. T. Mahan. (0-486-25509-3)

RENAISSANCE DIPLOMACY, Garrett Mattingly. (0-486-25570-0)

THE COMMUNISTIC SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES, Charles Nordhoff. (0-486-21580-6)

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF WEAPONS: ARMS AND ARMOUR FROM PREHISTORY TO THE AGE OF CHIVALRY, R. Ewart Oakeshott. (Available in U.S. only.) (0-486-29288-6)

THE BOOK OF THE CROSSBOW, Ralph Payne-Gallwey. (0-486-28720-3)

TATTOO, Albert Parry (0-486-44792-8)

THE NAVAL HISTORY OF THE CIVIL WAR, Admiral David D. Porter. (0-486-40176-6)

THE EXPLORATION OF THE COLORADO RIVER AND ITS CANYONS, J. W. Powell. (0-486-20094-9)

THE GEOGRAPHY, Claudius Ptolemy. (0-486-26896-9)

How THE OTHER HALF LIVES, Jacob A. Riis. (0-486-22012-5)

THE GREAT DIRIGIBLES: THEIR TRIUMPHS & DISASTERS, John Toland. (0-486-21397-8)

CASTLES AND WARFARE IN THE MIDDLE AGES, Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. (0-486-44020-6)

THE WANDERING SCHOLARS OF THE MIDDLE AGES, Helen Waddell. (0-486-41436-1)

ANCIENT EGYPT: ITS CULTURE AND HISTORY, J. E. Manchip White. (0-486-22548-8)

THE STORY OF THE TITANIC AS TOLD BY ITS SURVIVORS, Jack Winocour (ed.). (0-486-20610-6)

This Dover edition, first published in 1983, is an unabridged republication of the edition published by Public Affairs Press, Washington, D.C., 1948, under the title Gandhi’s Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Gandhi, Mahatma, 1869–1948.

Autobiography: the story of my experiments with truth.

Translation of: Satyanā prayogo athavā ātmakathā.

Originally published: Washington : Public Affairs Press, 1948.

1. Gandhi, Mahatma, 1869—1948. 2. Statesmen—India—Biography. I. Desai, Mahadev H. (Mahadev Haribhai), 1892—1942. II. Title. III. Title: Story of my experiments with truth.

DS481.G3A348 1983 954.03’4’0924 [B] 83-5353

9780486117515

Table of Contents

DOVER BOOKS ON HISTORY, POLITICAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCE

Title Page

Copyright Page

INTRODUCTION

PART I

I - BIRTH AND PARENTAGE

II - CHILDHOOD

III - CHILD MARRIAGE

IV - PLAYING THE HUSBAND

V - AT THE HIGH SCHOOL

VI - A TRAGEDY

VII - A TRAGEDY

VIII - STEALING AND ATONEMENT

IX - MY FATHER’S DEATH AND MY DOUBLE SHAME

X - GLIMPSES OF RELIGION

XI - PREPARATION FOR ENGLAND

XII - OUTCASTE

XIII - IN LONDON AT LAST

XIV - MY CHOICE

XV - PLAYING THE ENGLISH GENTLEMAN

XVI - CHANGES

XVII - EXPERIMENTS IN DIETETICS

XVIII - SHYNESS MY SHIELD

XIX - THE CANKER OF UNTRUTH

XX - ACQUAINTANCE WITH RELIGIONS

XXI -

XXII - NARAYAN HEMCHANDRA

XXIII - THE GREAT EXHIBITION

XXIV - ‘CALLED’—BUT THEN?

XXV - MY HELPLESSNESS

PART II

I - RAYCHANDBHAI

II - HOW I BEGAN LIFE

III - THE FIRST CASE

IV - THE FIRST SHOCK

V - PREPARING FOR SOUTH AFRICA

VI - ARRIVAL IN NATAL

VII - SOME EXPERIENCES

VIII - ON THE WAY TO PRETORIA

IX - MORE HARDSHIPS

X - FIRST DAY IN PRETORIA

XI - CHRISTIAN CONTACTS

XII - SEEKING TOUCH WITH INDIANS

XIII - WHAT IT IS TO BE A ‘COOLIE’

XIV - PREPARATION FOR THE CASE

XV - RELIGIOUS FERMENT

XVI - MAN PROPOSES, GOD DISPOSES

XVII - SETTLED IN NATAL

XVIII - COLOUR BAR

XIX - NATAL INDIAN CONGRESS

XX - BALASUNDARAM

XXI - THE £ 3 TAX

XXII - COMPARATIVE STUDY OF RELIGIONS

XXIII - AS A HOUSEHOLDER

XXIV - HOMEWARD

XXV - IN INDIA

XXVI - TWO PASSIONS

XXVII - THE BOMBAY MEETING

XXVIII - POONA AND MADRAS

XXIX - ‘RETURN SOON’

PART III

I - RUMBLINGS OF THE STORM

II - THE STORM

III - THE TEST

IV - THE CALM AFTER THE STORM

V - EDUCATION OF CHILDREN

VI - SPIRIT OF SERVICE

VII - BRAHMACHARYA—I

VIII - BRAHMACHARYA—II

IX - SIMPLE LIFE

X - THE BOER WAR

XI - SANITARY REFORM AND FAMINE RELIEF

XII - RETURN T

O INDIA

XIII - IN INDIA AGAIN

XIV - CLERK AND BEARER

XV - IN THE CONGRESS

XVI - LORD CURZON’S DARBAR

XVII - A MONTH WITH GOKHALE—1

XVIII - A MONTH WITH GOKHALE—II

XIX - A MONTH WITH GOKHALE—III

XX - IN BENARES

XXI - SETTLED IN BOMBAY?

XXII - FAITH ON ITS TRIAL

XXIII - TO SOUTH AFRICA AGAIN

PART IV

I - ‘LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST’?

II - AUTOCRATS FROM ASIA

III - POCKETED THE INSULT

IV - QUICKENED SPIRIT OF SACRIFICE

V - RESULT OF INTROSPECTION

VI - A SACRIFICE TO VEGETARIANISM

VII - EXPERIMENTS IN EARTH AND WATER TREATMENT

VIII - A WARNING

IX - A TUSSLE WITH POWER

X - A SACRED RECOLLECTION AND PENANCE

XI - INTIMATE EUROPEAN CONTACTS

XII - EUROPEAN CONTACTS (Contd.)

XIII - ‘INDIAN OPINION’

XIV - COOLIE LOCATIONS OR GHETTOES?

XV - THE BLACK PLAGUE—I

XVI - THE BLACK PLAGUE—II

XVII - LOCATION IN FLAMES

XVIII - THE MAGIC SPELL OF A BOOK

XIX - THE PHŒNIX SETTLEMENT

XX - THE FIRST NIGHT

XXI - POLAK TAKES THE PLUNGE

XXII - WHOM GOD PROTECTS

XXIII - A PEEP INTO THE HOUSEHOLD

XXIV - THE ZULU ‘REBELLION’

XXV - HEART SEARCHINGS

XXVI - THE BIRTH OF SATYAGRAHA

XXVII - MORE EXPERIMENTS IN DIETETICS

XXVIII - KASTURBAI’S COURAGE

XXIX - DOMESTIC SATYAGRAHA

XXX - TOWARDS SELF-RESTRAINT

XXXI - FASTING

XXXII - AS SCHOOLMASTER

XXXIII - LITERARY TRAINING

XXXIV - TRAINING OF THE SPIRIT

XXXV - TARES AMONG THE WHEAT

XXXVI - FASTING AS PENANCE

XXXVII - TO MEET GOKHALE

XXXVIII - MY PART IN THE WAR

XXXIX - A SPIRITUAL DILEMMA

XL - MINIATURE SATYAGRAHA

XLI - GOKHALE’S CHARITY

XLII - TREATMENT OF PLEURISY

XLIII - HOMEWARD

XLIV - SOME REMINISCENCES OF THE BAR

XLV - SHARP PRACTICE?

XLVI - CLIENTS TURNED CO-WORKERS

XLVII - HOW A CLIENT WAS SAVED

PART V

I - THE FIRST EXPERIENCE

II - WITH GOKHALE IN POONA

III - WAS IT A THREAT?

IV - SHANTINIKETAN

V - WOES OF THIRD CLASS PASSENGERS

VI - WOOING

VII - KUMBHA MELA

VIII - LAKSHMAN JHULA

IX - FOUNDING OF THE ASHRAM

X - ON THE ANVIL

XI - ABOLITION OF INDENTURED EMIGRATION

XII - THE STAIN OF INDIGO

XIII - THE GENTLE BIHARI

XIV - FACE TO FACE WITH AHIMSA

XV - CASE WITHDRAWN

XVI - METHODS OF WORK

XVII - COMPANIONS

XVIII - PENETRATING THE VILLAGES

XIX - WHEN A GOVERNOR IS GOOD

XX - IN TOUCH WITH LABOUR

XXI - A PEEP INTO THE ASHRAM

XXII - THE FAST

XXIII - THE KHEDA SATYAGRAHA

XXIV - ‘THE ONION THIEF’

XXV - END OF KHEDA SATYAGRAHA

XXVI - PASSION FOR UNITY

XXVII - RECRUITING CAMPAIGN

XXVIII - NEAR DEATH’S DOOR

XXIX - THE ROWLATT BILLS AND MY DILEMMA

XXX - THAT WONDERFUL SPECTACLE!

XXXI - THAT MEMORABLE WEEK!—I

XXXII - THAT MEMORABLE WEEK!—II

XXXIII - A HIMALAYAN MISCALCULATION

XXXIV - ‘NAVAJIVAN’ AND ‘YOUNG INDIA’

XXXV - IN THE PUNJAB

XXXVI - THE KHILAFAT AGAINST COW PROTECTION?

XXXVII - THE AMRITSAR CONGRESS

XXXVIII - CONGRESS INITIATION

XXXIX - THE BIRTH OF KHADI

XL - FOUND AT LAST!

XLI - AN INSTRUCTIVE DIALOGUE

XLII - ITS RISING TIDE

XLIII - AT NAGPUR

FAREWELL

INDEX

A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER - BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST

INTRODUCTION

I agreed to write my autobiography at the instance of some of my co-workers. Scarcely had I turned over the first sheet when riots broke out in Bombay and the work remained at a standstill. Then followed a series of events which culminated in my imprisonment at Yeravda. Sjt. Jeramdas, who was one of my fellow-prisoners there, asked me to put everything else on one side and finish writing the autobiography. I replied that I had already framed a programme of study for myself, and that I could not think of doing anything else until this course was complete. I should indeed have finished the autobiography had I gone through my full term of imprisonment at Yeravda, for there was still a year left to complete the task, when I was discharged. Swami Anand has now repeated the proposal, and as I have finished the history of Satyagraha in South Africa, I am tempted to undertake the autobiography for Navajivan. The Swami wanted me to write it separately for publication as a book. But I have no spare time. I could only write a chapter week by week. Something has to be written for Navajivan every week. Why should it not be the autobiography? The Swami agreed to the proposal, and here am I hard at work.

But a God-fearing friend had his doubts, which he shared with me on my day of silence. “What has set you on this adventure?” he asked. “Writing an autobiography is a practice peculiar to the West. I know of nobody in the East having written one, except amongst those who have come under Western influence. And what will you write? Supposing you reject tomorrow the things you hold as principles today, or supposing you revise in the future your plans of today, is it not likely that the men who shape their conduct on the authority of your word, spoken or written, may be misled? Don’t you think it would be better not to write anything like an autobiography, at any rate just yet?”

This argument had some effect on me. But it is not my purpose to attempt a real autobiography. I simply want to tell the story of my numerous experiments with truth, and as my life consists of nothing but those experiments, it is true that the story will take the shape of an autobiography. But I shall not mind, if every page of it speaks only of my experiments. I believe, or at any rate flatter myself with the belief, that a connected account of all these experiments will not be without benefit to the reader. My experiments in the political field are now known, not only to India, but to a certain extent to the ‘civilized’ world. For me, they have not much value, and the title of ‘Mahatma’ that they have won for me has, therefore, even less. Often the title has deeply pained me, and there is not a moment I can recall when it may be said to have tickled me. But I should certainly like to narrate my experiments in the spiritual field which are known only to myself, and from which I have derived such power as I possess for working in the political field. If the experiments are really spiritual, then there can be no room for self-praise. They can only add to my humility. The more I reflect and look back on the past, the more vividly do I feel my limitations.

What I want to achieve,—what I have been striving and pining to achieve these thirty years,—is self-realization, to see God face to face, to attain Moksha.1 I live and move and have my being in pursuit of this goal. All that I do by way of speaking and writing, and all my ventures in the political field, are directed to this same end. But as I have all along believed that what is possible for one is possible for all, my experiments have not been conducted in the closet, but in the open, and I do not think that this fact detracts from their spiritual value. There are some things which are known only to oneself and one’s Maker. These are clearly incommunicable. The experiments I am about to relate are not such. But they are spiritual, or rather moral, f

or the essence of religion is morality.

Only those matters of religion that can be comprehended as much by children as by older people, will be included in this story. If I can narrate them in a dispassionate and humble spirit, many other experimenters will find in them provision for their onward march. Far be it from me to claim any degree of perfection for these experiments. I claim for them nothing more than does a scientist who, though he conducts his experiments with the utmost accuracy, forethought and minuteness, never claims any finality about his conclusions, but keeps an open mind regarding them. I have gone through deep self-introspection, searched myself through and through, and examined and analysed every psychological situation. Yet I am far from claiming any finality or infallibility about my conclusions. One claim I do indeed make and it is this. For me they appear to be absolutely correct, and seem for the time being to be final. For if they were not, I should base no action on them. But at every step I have carried out the process of acceptance or rejection and acted accordingly. And so long as my acts satisfy my reason and my heart, I must firmly adhere to my original conclusions.

If I had only to discuss academic principles, I should clearly not attempt an autobiography. But my purpose being to give an account of various practical applications of these principles, I have given the chapters I propose to write the title of The Story of My Experiments with Truth. These will of course include experiments with non-violence, celibacy and other principles of conduct believed to be distinct from truth. But for me, truth is the sovereign principle, which includes numerous other principles. This truth is not only truthfulness in word, but truthfulness in thought also, and not only the relative truth of our conception, but the Absolute Truth, the Eternal Principle, that is God. There are innumerable definitions of God, because His manifestations are innumerable. They overwhelm me with wonder and awe and for a moment stun me. But I worship God as Truth only. I have not yet found Him, but I am seeking after Him. I am prepared to sacrifice the things dearest to me in pursuit of this quest. Even if the sacrifice demanded be my very life, I hope I may be prepared to give it. But as long as I have not realized this Absolute Truth, so long must I hold by the relative truth as I have conceived it. That relative truth must, meanwhile, be my beacon, my shield and buckler. Though this path is strait and narrow and sharp as the razor’s edge, for me it has been the quickest and easiest. Even my Himalayan blunders have seemed trifling to me because I have kept strictly to this path. For the path has saved me from coming to grief, and I have gone forward according to my light. Often in my progress I have had faint glimpses of the Absolute Truth, God, and daily the conviction is growing upon me that He alone is real and all else is unreal. Let those, who wish, realize how the conviction has grown upon me; let them share my experiments and share also my conviction if they can. The further conviction has been growing upon me that whatever is possible for me is possible even for a child, and I have sound reasons for saying so. The instruments for the quest of truth are as simple as they are difficult. They may appear quite impossible to an arrogant person, and quite possible to an innocent child. The seeker after truth should be humbler than the dust. The world crushes the dust under its feet, but the seeker after truth should so humble himself that even the dust could crush him. Only then, and not till then, will he have a glimpse of truth. The dialogue between Vasishtha and Vishvamitra makes this abundantly clear. Christianity and Islam also amply bear it out.

Autobiography

Autobiography